frame 28 August 2022

In Conversation:

Austin Collings with Ray Richardson

CHEERIO are thrilled to share this conversation between the inimitable painter and artist Ray Richardson and writer & filmmaker Austin Collings.

‘Ray Richardson’s paintings are more than just a mirror of everyday life. His subjects are drawn from his own experience of being born and bred and from living and working in London. When you look at the work of Ray Richardson you don’t have to experience it through just the usual suspects of art history. See it too through the minor musical language of Gil Scott Heron and Marvin Gaye or the pulp history of James Ellroy or the motivation of Cinema Noir.’ ©

Austin Collings is a writer and filmmaker. His last book God’s Fox was published by Pariah Press

He is also Creative Director of The White Hotel, Salford.

Ray's exhibition - 'SOULWEEKENDER' - is available for private viewings up to 45 minutes until the end of September.

Email: info@digbethartspace.com

Address: Digbeth Arts Space, Gibb Street, Birmingham, B9 4AT.

Ray Richardson (L) and Austin Collings (R)

funny guy, Ray Richardson

Nil by South by Austin Collings

I first met Ray Richardson through James Ellroy of all people. I interviewed Ellroy for the British Journal of Photography in 2015. He told me that he liked his art to be straight. That he liked what he called “good paintings”, which was shorthand for “no abstraction”. The thing had to be the thing that was painted.

And his favourite painter of things-as-they-should-be was Ray Richardson.

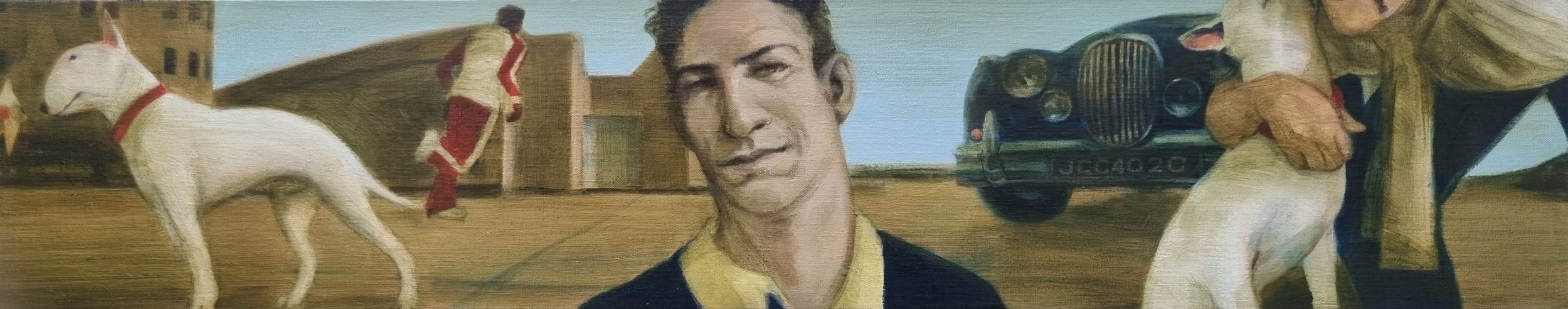

Ellroy owned three of Ray’s bull-terrier paintings. Bull-terriers are Ray’s signature. Like Trump, Hogarth’s ubiquitous pug, Ray’s own bull-terrier, Wee Bri’, often makes an appearance in his work. He is the canine equivalent of DeNiro to Ray’s Scorsese – GQ Magazine, in fact, dubbed Ray the ‘Scorsese of painting’.

I emailed Ray out of the electronic blue. I thought he should know that the self-named Demon Dog of crime fiction dug his work.

He was buzzing that Ellroy remembered him.

Talking to Ray is like overhearing uber-Cockney darts player Bobby George having a chinwag with Rembrandt in a South-East London boozer, if you can get your head around that oddest of odd couples. His accent is pure old London – I think he may be the most Cockney person I know. And like his busily calculated, alluring and stimulating paintings, he has a raw energy that seems to me like the very essence of urban romanticism.

Now 57, he was born in Woolwich and graduated from St. Martins School of Art in 1984 and then Goldsmiths in 1987. Damien Hirst was a fellow student.

Recently, Kay Fisher – owner of Digbeth Arts Space in Birmingham – asked him to ‘do a show’, as a favour. Not that Birmingham is below him, but he’s represented by the prestigious Beaux Arts Gallery in London and certain artists are precious about all that, showing at a ‘smaller gallery’. Not Ray. He loved the idea despite the last three times he has been to Birmingham.

Ray’s first visit was in 1976, as a schoolboy just turned 12. ‘Our school – Roan Boys School - had won the London Cup kind-of-thing. So, we represented London in the Under 18’s school boy’s FA Cup Final. We had to play the team that won from greater Birmingham. The whole school went en masse to St Andrews – Birmingham City’s ground - to watch the game. Our side had four players who went on to become professionals after they left school and they battered them 4-1. All our buses outside St. Andrews were getting bricked after the game, windows smashed. Worst part, we all had to wear our school uniforms and they’re all wearing Birmingham City tops and scarves, all with long-at-the-back feather cuts.’

The second visit was almost as unsuccessful. ‘There was a league game at St Andrews and we - Charlton – won and we got chased. I was quite young then but these older bunch of lads I was with wanted a row but I just wanted to get-going.’

‘Last one was when Charlton played Leeds in the inaugural play-offs in ‘87. It was my folks wedding anniversary. We were sharing Selhurst Park at the time with Palace. We won the first leg 1-0. Second leg was at Elland Road and we lost that 1-0. So, we had to have a decider at good old St Andrews and we ended up beating Leeds 2-1 in extra-time and we got promoted. This was just before the Premiership started and so this was the first time, I would see Charlton in the top-flight. There was about 25,000 Leeds fans and 5,000 Charlton. We came out of St Andrews and the police said: ‘The bullring is that way. Start running.’ We got down to the bullring and all these Herbert’s stepped out of the shadows saying: ‘Who are you?’ ‘We’re Charlton’ And they said: ‘Get going.’ They were waiting for Leeds. All the Blue-Noses were waiting there to have a go at the Leeds fans. They’ve got proper bit of history between them. Leeds have history with everybody, a bit like Millwall. They make their own history.’

Ray’s Digbeth exhibition, entitled SOULWEEKENDER (Ray is into his soul music. It runs deep in him), goes the other way. It’s a corker.

Digbeth Arts Space has a look of the white bedroom that appears at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey – the bedroom at the end of the universe – which was originally designed by Harry Lange, who had previously worked for NASA. Natural light leaks in and dies out from a domed window in the ceiling. I don’t like the word ‘space’ when used in artistic terms. It’s a room. And room is a much better word. But this white Kubrick-set in Digbeth has a genuine feel of space. 2022: A Birmingham Odyssey.

A mate of mine bought one of Ray’s paintings that night on an instalment plan without telling his girlfriend. Hungover the following day, he had to explain this investment to her. He wasn’t drunk. He’d only had two bottles of beer. He just had to have the painting. It’s that good.

‘She slammed the phone down on me,’ he told me.

At his very best, Ray applies paint as if it were a primal fluid. His brush work has an athletic velocity. It’s eloquent, fast, sensuous, subtle. The paint never knew how wonderful it was, until it hit the canvas. The colours call to mind the past that made them. Faces look back at you like a butcher’s windowed pig. Body parts reach out, like friends, shaking your hand or fist-bumping you outside a pub. The skies are a curious blue. The peach clouds accent the dynamic harmony.

There’s a certain Grand Theft Auto style glamour to some of the canvases. But it’s GTA: Miami seen on a mate’s plasma when he’s stoned and playing video games in his flat: not, in other words, the real thing. But then sometimes, like when you’ve nowhere else to escape to on a Friday night, the plasma Miami is good enough..

These urban landscapes are where people get on, or try to, looking for a break. Humanity is still an intimate mess, but there is hope amidst the squabbles. This isn’t nostalgic conservatism. Nor is it modern liberal doom. Here, he doesn’t pull inward so much as upward, towards some greater beyond, another world’s promise.

‘The drama is heightened by the way the images are cropped,’ he tells me. ‘It increases the intensity. There is always a sense that something else is happening outside of the frame. Or something has happened just before you’ve entered the frame. You don’t know whether there’s a narrative going on that you can’t quite follow as if somebody has said something prior to the painting and you’re not going to see the consequences either. I like all of that.

It’s that thing when you’re on the phone and you don’t want people to hear what you’re saying, or when you’re a kid and the phone is right by the living room and your old man can hear you but you don’t want him to hear you. All that sort-of thing about hiding stuff – but maybe not overly serious stuff – which we all do. I try to imbue my paintings with that sort of everyday tension.

brand new second hand, Ray Richardson

There’s that great scene in Heat with DeNiro and Pacino at that table. They’re shooting over the shoulder. Neither are giving up ground. I think that enters everyday life. There’s so much second-guessing in life. People not saying what they’re thinking.’

In the paintings, something may have already happened or be about to happen. You’re in that frozen moment. In that in-between. Is there going to be a resolution or something more severe?’

He cites Get Carter and Mean Streets as chief influences (two films that he rewatches and refuels on endlessly, when his wife isn’t in), but I see more of Gary Oldman’s autobiographical South East London-set directorial debut Nil by Mouth. Often when people look back at this masterpiece, they only remember the domestic hell, the agg’, the tense calm after the devils- dandruff-dust has settled which Oldman depicted so unflinchingly, ghosts stabbing at the memory of where he came from.

But, much like in Ray’s paintings, there are overlooked moments of tender insight and humour in Nil by Mouth. Also, Oldman doesn’t establish characters and relationships in a traditional text- book film sense. He plunges you into the pub-and-high-rise-mix and you go along with the relationships, and the heavy nights, as you would if you’d just met them. It’s up to you to work out what’s happening: who belongs to who and who doesn’t belong to who and who would rather be away from it all, not belonging to anybody. This act of plunging reminds me of Ray’s paintings.

‘You don’t always see the world nice and level,’ he says, explaining some of the odd angles he paints, those jagged pyramids of knees and elbows. ‘Sometimes you may be falling over.’

‘I’m always aware of things disappearing off the edges. I don’t stop a film, freeze-frame it and think: I’m going to draw that. I’ll draw when I’m watching things, really sketchy. Just as a note. Then I’ll piece it together on the canvas. It’s about catching that fleeting moment but not in an overly representative way.’

‘Like capturing phantoms?’ I ask.

‘Yeah, like capturing phantoms.’ He replies.

‘Like epiphanies as artistic radiance?’ I ask.

‘Yeah, sort-of...’ He replies, smiling, not quite having too much fancy-talk. Keep it real son.

‘There’s a bit in the book of Get Carter’ – written by Ted Lewis – ‘which fired my head off. He’s in a club and Lewis writes: The place was juicily carpeted. It was that kind of place’ When I saw “juicily carpeted” I thought: that’s a title. I went off and did a painting with that title. But that related to my own life working with my dad when I was at art school. He was an upholsterer. I used to go and fit the pub furniture with him. Deep-buttoning. Old school diamond shaped thing. Old school pub furniture. Before I went to art school, I’d be going to shit-hole pubs on the Caledonian Road at four in the morning owned by brick shithouse Irishmen.

My old man actually pulled me out of secondary school in the fifth year for two weeks one time to help him work on a job. Somebody grassed me up at school. I got called in from the deputy head.

‘Word is on the street that you have been out working with your dad.’

My arsehole is making chocolate buttons, and I’m lying through my teeth.

All these pubs were juicily carpeted. Stinking. There would be all those swirls on the carpet and the wallpaper.’

*

way way back last week, Ray Richardson

Each blank canvas is like a semi-final to Ray Richardson. He loves the thrill of getting the initial idea – that gee-whizz moment – but then he has to paint the thing, has to progress to the next stage, in order to keep reliving the thrill of a possible final (that never comes).

‘I’m guessing you have to be charged by your own paintings – otherwise you wouldn’t continue.’

‘I’ve got a painting of a seascape in my spare bedroom in our flat. It relates to me splitting up with my first wife. It’s a seascape in Ostend, Belgium. It’s a belter. Some people might think that’s a bit weird having a painting about breaking up with your first wife. But I find it weirdly soothing. It was a penny-drop moment. When I saw the sea, I knew: this is all over [he means the relationship]. I had to get it down. A symbol of our separation. The separation didn’t happen until a while after but that was the moment. All your years of relationship – 14 years – flashing before your eyes in front of this seascape.’

Interesting that he makes the connection with water. Both Get Carter and Mean Streets end dramatically with scenes of water and death.

‘Growing up in Woolwich, I took it for granted that you had water nearby. You’d see the river all the time as kids. But I didn’t cotton on to how magic it really was at the time, living by the Thames. As I moved back to Woolwich, I realised how important the water was to me. The Thames is alive. You go to Paris: the Seine is beautiful but there’s no tide. The Thames is alive with cross-currents. I see it all the time.’

And Ellroy: when did he last see him?

‘I met him in London last. He was staying in some hotel off Northumberland Avenue. He wanted to meet me and Wee Bri’. He came down and he had a Hawaiian shirt on. He’s really languid. We sat down on the steps on this very swanky hotel.

He says to me: ‘I’ve been invited to some really shitty party. I’m picking up the Writer of the Year Award. I wish I could take you.’

People are just coming in and out of this hotel and it looks like they’ve bought half of London with all these shopping bags. Limo’s pulling up. Top hat characters opening doors. And me and him are sitting on the steps, with Wee Bri’ there. One of the top hat characters says: ‘Excuse me gentleman, I’m going to have to ask you to move.’ Ellroy was really nice, saying that he was a guest, but fine, I’ll move. These stairs were about thirty-fucking-foot-wide but they didn’t want us loafing around, spoiling the image. So, I took him up to my mate’s pub called The Marquis.

He had a coffee. I had a pint. Next day, the owner comes in asking me why I didn’t tell him I was bringing Ellroy in? It’s not the sort of thing you really tell somebody is it?’