frame 47 January 2024

Belonging

by Francis Aidoo

Francis Kofi Aidoo is a youth mentor/writer from south London. He has written mostly for the theatre and his work tackles themes of family, belonging and the duality of identity. He has a keen interest in exploring characters on the edges of society and he's currently working on his debut novel PAVEMENTS.

I have brief snatches of memories from my childhood in Accra, fragmented pieces of an unfinished puzzle laying strewn across my mind that only when looked at from a distance begin to form an image of my life. Until the age of seven, I had only known one mother, one home, one name, Kwame. I had no idea I belonged to anyone or anywhere else in the world. There was no desire for the duality that would be forced onto me. I had no need or want for a new name that would be more acceptable - that would allow me to fit in easier. In moments of stillness, eyes tightly shut, I'm gifted this black blank canvas, as if a screen at the cinema before the projector starts rolling. There I am the powerless protagonist starring in my own movie. I have very few regrets in life, not remembering what my grandmother looked like would be one, I feel her presence more than I can picture her face. She feels like sunshine, a warm protective glow. The first person I loved before I knew what love was.

A stamp from Accra, Ghana

The day the letter arrived, my childhood as I had known it ended. In an excited voice, I was told I would be joining my mother in London. I knew I was meant to feel something - joy, relief, happiness - yet I was numb. I was filled with questions, where was London? Who was this woman that was meant to be my mother? Would I ever come back? Why would I have to change my name? I tried to make sense of the situation, my mouth would open then close, moving rapidly yet no sound escaped the bottom of my dry throat. I just stood frozen in disbelief as tears streamed down my face. Even then as a child, something inside me understood these were the last moments I would have in Ghana.

Here was London, welcoming me with its tapioca coloured skyline, bitter winter wind, noisy streets, in the mid-1980s. I arrived with everything I owned packed neatly in a small burgundy Delsey hard shell suitcase. My hands gripping onto the handle as if inside I had smuggled out the finest of Ghanaian gold, not the mundane necessities of travel, such as pants, socks and singlets (my grandmother's term for vests). I stood for a moment, cold and uncomfortable, not realising how out of place I must have seemed. Dressed as if I was on safari in the 1920s, a thin khaki flannel suit that did nothing to stop the cold seeping into my bones, I felt naked. I wanted to go back home, where I had no need for tight leather shoes that imprisoned my feet or buttoned up suits that hemmed me in as if I was encased in a coffin. I wanted to feel the dusty earth underneath my bare feet, to run until my lungs ached, yet I knew I would never feel that freedom again. If my mother and I embraced that day, I have sparse recollection. Somewhere the seven-year-old me believes we did, or maybe needs to. Maybe it lasted a while, maybe it wasn’t a clumsy awkward attempt at rekindling emotions foreign to us both. Maybe.

To begin with my brother, mother and I stayed in a hostel alongside other migrants. My mother had been placed on a waiting list for a council property. These temporary accommodations were commonplace before a move to a more permanent residence. It was crowded, noisy and for me very confusing, as I spoke and understood very little English. This would make primary school a minefield of bullying, taunts and endless fighting, leaving me with a feeling of otherness that still lingers to this day. I was teased for wearing national health glasses, having a thick African accent, wearing clothes that never fitted as they would often be hand me downs worn by my brother and my rough uncombed afro hair was another source of ridicule. I stood out, I didn’t belong. At an early age I discovered my fists would be the solution. When the outcome is a mouth full of blood and loosened teeth, it makes others think before they speak. I was fluent in the language of violence and that requires no elucidation. The bullying and taunts of “African bubu” soon stopped.

The first place we could really call home was on the Badric Court Estate, a sprawling spider's web of concrete slabs, brutal muscular architecture at its post war finest, housing thousands of London’s forgotten tribes. Everyone I knew lived on an estate with little or no contact with their fathers. If we were poor, we didn't know it, if we were disadvantaged, we didn't feel it, this was our normal. For the first few years I attended what was classed as a "good" school but by the time I began my second primary school we had been forced to move again. Sacred Heart was no St Joseph's, things rapidly began to deteriorate at school and at home.

Badric Court Estate

Looking back, you realize life is about the ‘What ifs?’ and ‘What could have beens?’. Rizla paper thin moments that can go on to either weigh you down or untether you of all burdens in the future. Leaving St Joseph's primary would become one of those moments. I craved stability. Boring, monotonous consistency, however, I was handed upheaval and change yet again. My mother would remind me constantly how out of all her children, I resembled my father the most - I soon realised that this was not meant as a compliment. The mind has a way of protecting us from ourselves. I had convinced myself quite early on I was happy knowing very little of my father, a father to me was like a kidney, you could lose one and still function.

Out of all the friends I made during my school years, only one had an active father in his life. Sean was very close to his parents and as a child I felt at times pangs of jealousy when around his house. Seeing how they were as a family, a real unit. We would tease him for being a 'mummy's boy', mostly out of envy. Then in 1994 Sean’s father suddenly died of a heart attack. Sean was never the same, he became reclusive. The older we became, the more he seemed to live life very close to the edge, almost as if he felt he too was on borrowed time, thinking he would also die young. None of us had dealt directly with death before and we had no idea what to do, so we often just sat with him in awkward silence. Secretly I felt a selfish sense of relief that I would never have to experience this level of pain. I didn't have a close connection with my own father. I began to appreciate the detachment I had from him. To me, the stronger you were, the less emotions you showed. Emotional pain was frightening, you could not escape it, it was in you, deep in your soul. Physical pain had become easy to cope with, after you experience beating after beating your body becomes calloused to the slaps, your ears become deaf to the shouting. You can detach your mind from your body very easily. At first you cry a lot from the shock of a hot palm across your face, then after a while you can clench your teeth and just take it. I had hated myself for crying, whimpering like a hurt dog, so soon I just stopped and would stand silently taking my beatings for any minor infraction. The only thing that kept me going was knowing soon it would be my turn to do the same to others. I was a walking grenade, waiting to be tossed into society with the pin pulled out. I was a loveless, fatherless, angry young man just waiting to give back all I had received.

I had always felt a cold distance between my mother and I, and whatever feelings I would have had for a father, mine was not around to receive them. For the longest time I convinced myself I was adopted and somewhere out there were my real parents waiting to swoop in and take me away.

Many nights I told myself if I just prayed on it long enough, God would answer my prayers, that was the least he could do. I spent every Friday and Sunday in church, and I felt like God owed me. He was in my debt. I wasn't being greedy, I didn't pray for toys or clothes, I just wanted two things from God: my real parents to find me and to be good. There is a phrase in Twi that is tattooed into my mind 'akwadaa bone' which means in English 'bad child', a phrase I was called so often, I soon began to believe something inside me was rotten. I would wait until the dead of night, clench my hands tightly as if they were glued together and plead to be good, just to be good.

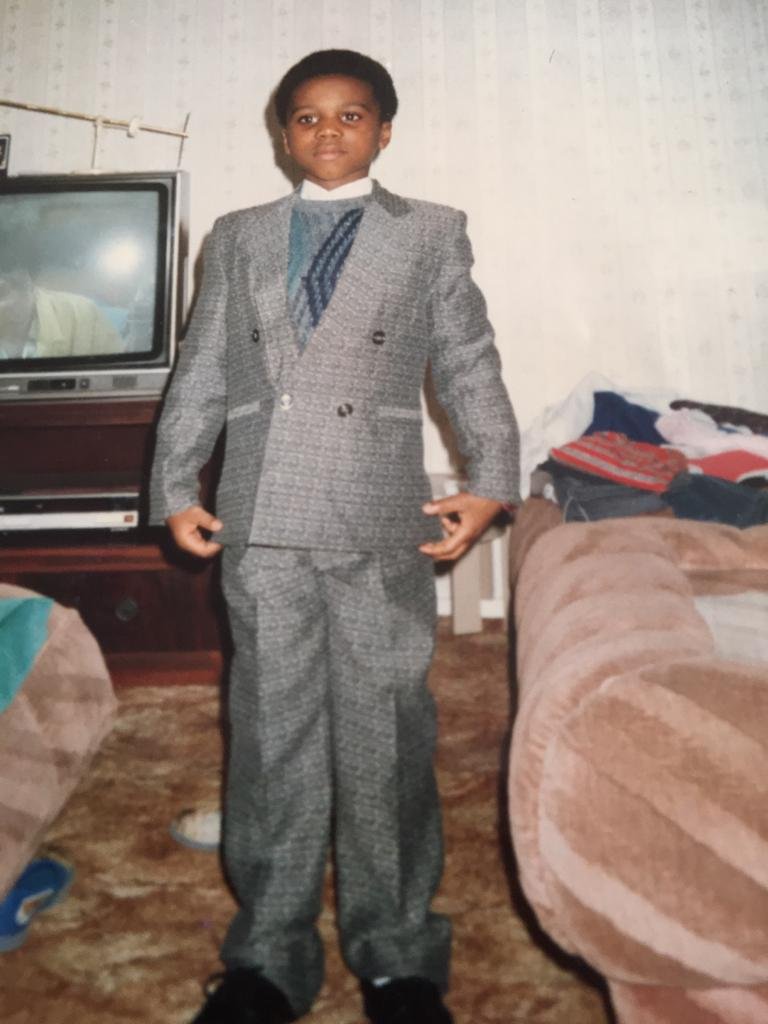

The author as a child

There were moments of happiness, slim vignettes of what childhood could be. These moments would be violently punctured by chaos and upheaval. I began to feel the most relaxed within struggle and pain, happiness made me uneasy, gentle people made me suspicious and affection made me itch. When my father did turn up, the arguing would progressively worsen between my parents, from shouting to breaking plates to physical violence. My mother was a strong woman, still the strongest person I know. She knew nothing of comfort, she just worked for years. She often had two, sometimes three jobs, which meant very little time for anything else or herself. My father had little formal education. He had always been someone who survived off charm and a ready smile. He could take a fifteen-minute walk and make three new best friends. He was handsome, quick tempered, with a typical paunch of a man who enjoyed Olympic sized portions of fufu peanut butter stew with meat tucked underneath, a prize to be found by the greedy consumer. He would fish his large fingers through the thick rich stew for treasures of succulent cuts of lamb that were eaten till you could suck and chew down on the bone with a crunch as it snapped apart. A trick he swore made your teeth stronger. His paunch was always stylishly covered in one of his flamboyant shirts which gave him the look of permanent pregnancy. He was a man of intense contradictions: a ladies' man who would have one real love for the rest of his life, a family man who never quite knew how to keep his own together, an electric anger which like lightning would strike white hot yet dissipated just as quickly. He had a smile which took up most of his face and a front gold tooth that glistened. I had wanted to be just like him, even down to his stammer which made calling my name sound like an engine struggling to turn over ‘Je..Je.Je..Jeffrey’.

I liked my father, but I couldn't say I loved him. Yet I had a love for my mother, however at times I didn’t like her.

My mother conflated anything she saw as flashy or attention grabbing with negativity. There is a common misconception that the racism and prejudice experienced by migrants in the early 80's could be isolated between white British and black migrants. What is often left unsaid is the internal fears and catastrophic stereotypes internalized then spewed amongst the black diaspora. Some of the early Caribbean and later African migrants were fed false and damaging narratives, such as the lazy, weed smoking Jamaican or the starving, uneducated and uncivilized African. Things I inherently knew to be stupid on both sides. Something as simple as having a gold front tooth was seen by my mother and others in our small Ghanaian community as a brash sign of bad intent reserved for the Jamaican rude boy. Often I was not only fighting racism from whites, I would be fighting prejudicial views based on ignorance held by fellow blacks, often through their lack of interaction and understanding. I was always proud to be African, yet many were not, and they would lie about where they were from to avert any bullying or inadequate feelings. Girls would openly say they wouldn't date an African bubu, with such vitriol it pierced your chest. I was fortunate enough to grow up amongst a mixed estate, so after a while we began to slowly see past the nonsense and the lies we had been fed about one another.

I know very little of how my mother and father met. It felt alien to me that at one point these two individuals even loved or cared for each other enough to have children. Many nights I would sit at the top of the stairs with ring-side seats to this circus of destruction, looking on as my father slapped my mother over and over. I sat holding my breath in fear of being heard or seen, with each slap her body would begin to crumple, she would fall as if in slow motion to her knees crying, begging him to stop and I would feel charges of anger surging through my body. I wanted to yell 'STOP!', yet I sat silently and watched as tears of rage and helplessness filled my eyes. I feel ashamed to admit it, but part of me wanted her to be as helpless as I was when she beat and slapped me. In my mind this was some sort of payback, so like a coward I did nothing. As time went on, I became proficient at holding in secrets, my only release was school; it was the only place that offered me consistency. I hated inset days, bank holidays and dreaded the six-week summer break. I didn’t want to be home.

The day my father left for good I had been suspended from school this had become a somewhat familiar occurrence especially when you have a temper. Unsure how I would break the news to my mother I began the long walk home, it was as if a condemned man been sent to the gallows. With each step my legs began to feel heavier and heavier. I wiped the building sweat off my forehead as my throat began drying up, I began to rehearse over and over how to begin the conversation. By the time I had almost reached home I was convinced I was Horace Rumpole. I would fight to keep my client from their pending death sentence. I decided I would tell her the truth, well just enough of the truth to buy me some sympathy. I would tell her I was minding my business (which essentially is kind of true), I would tell her I was defending her honour. I would have to add, I was doing my work, of course. I would leave out the fact I was teasing Ernest at the time, but that’s a small detail, she wouldn't have to know. I had asked him for two pound for the tuck shop and not only had he said 'No!' he had added the two words that would automatically guarantee a fight ‘Your mum!’. We knew if a sentence began with ‘Your mum’ it would end in a slur. That was it! What could I do? The gauntlet had been thrown, that was a declaration of war amongst all young boys. I grabbed him by his tie, pulling him close enough for me to rain down as many punches as I could, his nose exploding on my fist, blood running through my fingers with each punch. The deputy head was called and I was dragged to the headmasters office.

The journey home had been a blur, my body already flinching as I nervously started to put the keys into the door, but it was already open. I panicked, had I forgotten to lock the door? Or, even worse, had someone broken in? I tentatively pushed the door open, fully stepping inside and scanning the place for signs of an intruder my eyes only saw her, knees tucked to her chin, her arms wrapped around herself, rocking in an empty living room. The tv gone, settee gone, tables, chairs and pictures all gone. The house was bare, I called out to her 'Mum, what's happened, have we been robbed?' She just rocked unresponsively, momentary silences punctuated by sniffling and whispers of 'He's gone, he's gone and taken everything!' I ran into the kitchen and that too was bare, he had even taken the bulbs. I'm sure if he had time, he would have taken the doors off the hinges. My head was spinning, I steadied myself walking back slowly into the front room. I sat with my mother and that was the first time she had really hugged me. I cried not over him leaving, but because it hurt to see my mother like this.

From then on, true happiness frightened me, it never arrived alone. I grew to distrust myself for smiling too long, laughing too hard, I knew I’d have a debt outstanding. I learnt to pay my balance early, hiding my smile, pushing my happiness down where it wouldn’t be discovered and stolen from me. Soon I worked out that if I stayed in the dark it could never surprise me, I was not going to be Sisyphus, rolling my emotions like a boulder up and down this hill.

My brother Simon and I were nothing alike. As a child I looked up to him, he was the person I hoped would offer me some protection, yet I never considered how he must've been feeling trying to make sense of the madness around us. The time we had spent apart as children had affected the bond that we should have shared. We were three years apart, yet it may as well have been a lifetime. He was an altar boy, captain of the school football team, well-liked by the teachers and fastidious with his appearance. I would have stolen the church offering given the chance, had no interest in sports, was tolerated by most of the teachers and I didn't care how I looked. Some days I would be sent to school in my brother's hand me downs, even having to wear his old school shoes stuffed with socks as his feet were much longer than mine. I sensed a feeling of embarrassment from him about living where we did. Being children who had to use dinner tickets in school to receive our free meals. I began to slowly identify everything he was and wanted to be the opposite. My brother would spend as much time as he could out of the house and out of the area. Our relationship would slowly deteriorate, we had nothing in common and I preferred it that way. I was not embarrassed about coming from a council estate, in fact it was something I became proud of. For me there was nothing better than being from South London.

The author as a child

I would often wonder, of all the places I could have ended up, why here? When looking out my living room window I would see houses worth millions, a stone’s throw away from my estate - a future King would be attending one of the most exclusive private prep schools in the country, St Thomas's in Battersea, located yards from our state school. I would walk past every morning wondering what their lives must be like. My bedroom overlooked a football pen which was rarely used, becoming more a landmark for local drug dealers to meet customers. I never learnt how to ride a bike or attended any sleepovers. I wasn't allowed to play outside which would become as much a blessing as it would a curse. Not being allowed out kept me isolated from any real trouble on the streets, yet also built up a hunger inside of me to discover what I was being kept away from. I was like a dog on a leash each day, bit by bit, gnawing away at the rope until I would become untethered and free to do what I wanted.

My time in Ghana was now a distant dream lived by another person I once knew. I moved from one imposing grey bricked estate to another. Scholey housing estate, near the equally notorious Winstanley Estate would be the last family home we all would share. Outsiders referred to us as living in Battersea, yet my friends and I would grow to hate that. Battersea felt too gentrified, we would prefer 'Junction'. To us the whole of Battersea was just 'JUNCTION'. For young boys who had very little to call their own, this would be ours, in all its dilapidated glory. We grew up understanding we were marked for failure, so took everything given to us as a negative and stood it on its head, making it something we would be proud of. From the way we dressed, to the words we used to describe one another or the things we had. We aspired to be bad, bad wasn't a derogatory term, to us bad meant good. If somebody dressed well, we called them trash or trashy. We didn't fit into society and had no desire to, we would form our own.

There is a common misconception surrounding young men in inner cities and crime. One that’s oversimplified then regurgitated as gospel by the media. The role of a modern day 'Fagan' taken up now by an ‘older’, who stalks the streets enchanting young men with tales of ill-gotten riches, alongside offerings of chicken and chips from the local Morley’s and promises of cocaine white air forces and any refusal being met with a beating. This is how we are told grooming works. That is a fairy-tale, I can give you a fairy-tale or a truth. Yes, I was approached many times by 'olders' in the area or surrounding estates, who would offer work or access to join a gang. I was able to always say ‘No’ without fear of reprisal. I said ‘No’ not because of any moral misgivings on what I was being offered, I refused mainly because I had not grown up hanging around these people and felt no affiliation to them. My mother's insistence on keeping me in the house the majority of the time provided me with a reliance on myself. I didn't seek to be part of any group, for once not belonging became a power. I had made up my mind from a very early age I would not join the local boys robbing, stealing or selling drugs. I promised myself whatever I was going to do, I would do it on my terms and by myself. I had spent years quietly observing the world outside my bedroom window, studying the life I was eager to enter. I had watched my mother work day and night just to survive. I would see the morning aunties and uncles like zombies, either coming back from or going to an all-day cleaning job. We wanted better, we wanted more, we were not going to settle. Our parents had seen themselves as visitors in a foreign land, always wanting to be out of the way, keeping themselves small and just getting by. After a while we were not just the children of migrants here to just keep our mouths shut, head low and to stay out the way. No, we belonged and we were here to take what was ours. To take up space. Call it arrogance, we called it self-belief. We were going to make it our own way, fuck the consequences. We would put our freedom, our bodies and for some of us our minds on the roulette wheel of life and bet it all on black.