LONG READ 11

August 2021

David Keenan: MONUMENT MAKER

By Cosmo Landesman

David Keenan Cosmo Landesman

This week's Long Read celebrates one of the most exciting fiction releases of the summer: David Keenan's visionary magnum opus, MONUMENT MAKER, which came out last week. Freelance journalist Cosmo Landesman spoke to the author about dedicating his book to 'the glory of God', hearing voices during the writing process and why reading for Keenan is all about pleasure and awe.

In his fiction, novelist David Keenan celebrates the uncelebrated: small towns, forgotten lives, invisible indie-bands, mysterious cults and Perry Como. His second novel, For The Good Times (2019) - set in Belfast in the 1970s - won the Gordon Burn prize for fiction. Now comes his fifth and most ambitious novel yet: Monument Maker. It’s a big book (over nine hundred pages) that took Keenan ten years to write - and if you’re a slow reader like me, it will take you ten years to read. So take my advice. Don’t read it. Smoke it. Snort it. Swallow it.

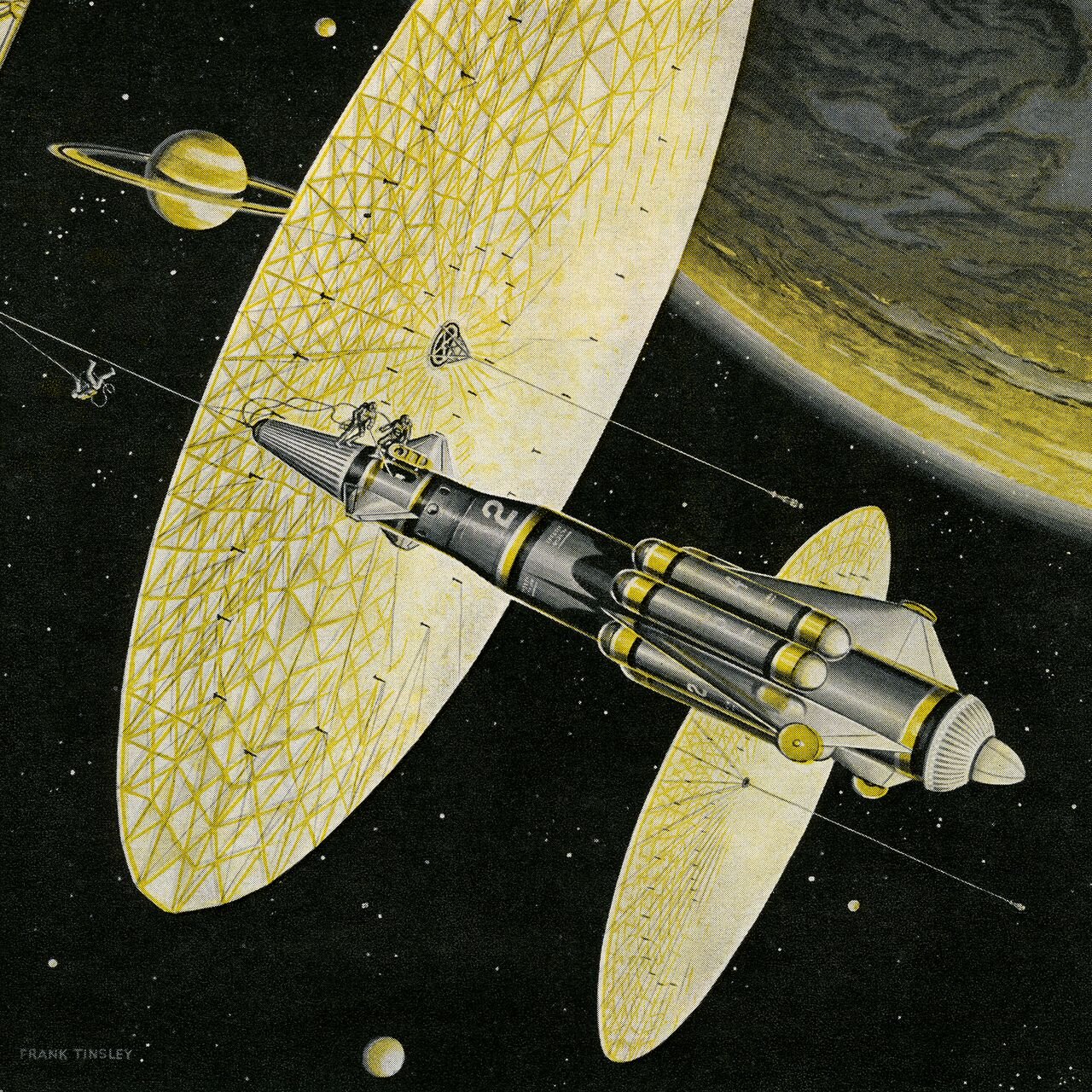

It’s not a novel. It’s an acid trip. A freaky, feverish dream set in print. Baroque and bizarre, Monument Maker is a literary cathedral designed by Mad King Ludwig II, with help from Burroughs and Arthur C. Clarke. The book spins the reader through the rectum of history and dumps you in the mosh pit of heaven. Oops. Sorry about that. I got a bit carried away. I blame Keenan. His incantatory story telling makes the standard language of literary profiles and interviews seem so puny and prosaic you have to pump up the volume and go weird to convey the wonders of his fictional world.

What’s Monument Maker about? God? Art? Love? Time travel? Cult connections and failed erections? Search me. What does Keenan think? He’s not big on what’s-it-all-about questions when it comes to his work.

“I’m not interested in books with a point or a lesson. And I’m not interested in plots. Reading for me has always been about pleasure and awe. When I sat down to write it in 2008, I had no idea what it was about.”

And now that you’ve finished it?

Keenan talks about “resurrecting the dead” and the grief of his gran and God knows what. He’s on record as saying that the book is “a monument to all the sweethearts separated in time and to the cruelties that tore them apart and the summers separated in time and to the summers they once loved it.”

But even that’s inadequate. Asking what this novel is about is the wrong question. A better one is: why did Keenan dedicate his book “To the glory of God”?

Keenan says, “I think literature should show us how spectacular, miraculous and unique existence is. I wanted to thank God for the moment, for the miracle of life. So many books these days are just dreary critiques. I wanted a book that said YES! A book that was grateful to the glory of beauty and love and art.”

Keenan believes in God - “I’ve always been religious” - and he believes in Art. “I believe art can transform your life - it’s true because it transformed mine.”

He is trying to give literature back its magic; its ability to inspire awe and wonder in the reader. Yes, that sounds rather grandiose but Monument Maker is devoid of goody-good solemnity; it’s fun and filthy. “I like writing about sex!” says Keenan. He does it well, too; “The lips of her labia are felt grey, mouse eared." And it has some surprising shards of poetic insight; "A statue is a light that has held its breath.”

How do you actually construct a novel like Monument Maker? Given the sweep of its narrative - it moves between the battle of Khartoum in 1884, to the Second WW, to the present - and characters that proliferate like dividing cells under a microscope, you’d think it was a novel that was meticulously planed and endlessly revised. So how did he do it?

The short answer is he didn’t. It was the voices in his head that wrote it. And I don’t mean the voices of the writer’s imagination; we’re talking other worldly voices. Supernatural stuff. He hears dead people.

“There were these voices, voices of the dead just speaking through me. It was a kind of possession. I didn’t have any control. I didn’t plan or rewrite the book. I didn’t take notes. It just wrote itself.”

William Blake, The Good and Evil Angels, 1795–?c.1805.

Keenan makes his writing sound like spiritual visions expressed through acts of literary exorcism; William Blake meets Linda Blair. Such was his all consuming obsession with his book it put his mental health in danger.

“I began work on it in 2008 but stopped after a year. It started to worry about my mental health. I was losing who I was and wondering if David Keenan even existed. It was like looking into the abyss. I was suffering from a kind of psychos."

Did you think you were going mad?

“There were times, yes. Fortunately, my wife told me to walk away and leave it for a year.”

How do you write a novel of this size and scope?

The hi-energy gonzo-ness of his writing suggests an author fuelled by stimulants when he sits down to write. I imagine Keenan in his study reaching for the whisky, the opium pipe, and heaven knows what to a blast of full volume trash-metal and Wagner.

But no. Keenan requires nothing but silence to write.

“I need silence to hear the voices, so I never play music.”

William S. Burroughs, Cosmic Sad Clown He Knows the End. He's full, 1993

William S. Burroughs, The Melting Red Disease, 1988

I wondered how Keenan is going to follow a ten-year-in-the-making novel like Monument Maker? Is he burnt out? Does he need a break? No way. Keenan has three new novels all finished and awaiting publication.

“Two of them are prequels to my first novel This Is Memorial Device and the third one is a memoir about my relationship with my father and my adventures in Mexico.”

Growing up in Airdrie, a small town about 21 miles outside of Glasgow, Keenan was a self-professed teenage “geek”, obsessed with science-fiction, Dostoyevsky, Heavy Metal, fanzines, Lester Bangs, Burroughs, Lermontov, Picasso, Tarot Cards and Throbbing Gristle.

Has he changed since those days?

“Oh god no! I Saw my mum the other and she remarked that I was exactly the same person I was when I was a teenager. And I think she’s right.”

Let’s hope that Keenan never grows-up and stops being the bold and brilliant geek of British fiction.