LONG READ 10

July 2021

The Visitor Sees Beauty

By Ralf Webb

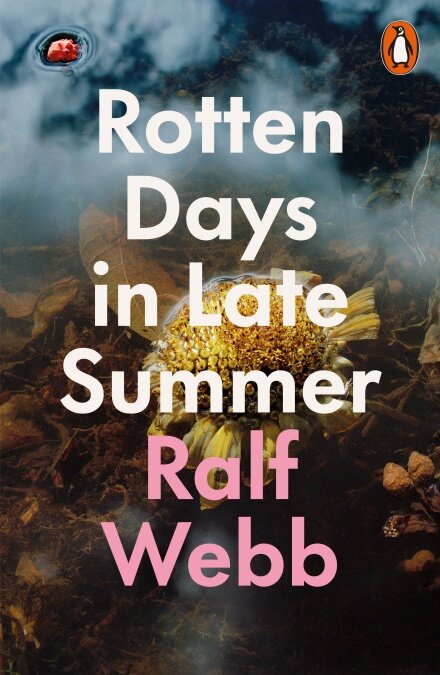

This week's Long Read comes from Ralf Webb, former Managing Editor of The White Review, whose debut collection of poems, ROTTEN DAYS IN LATE SUMMER (Penguin, 2021), came out in May. THE VISITOR SEES BEAUTY discusses place, dream-selves, the pastoral and why the landscape of the West Country haunts the collection.

A few weeks ago, I was out with some friends in Walthamstow, at a pizzeria. The evening was going well – I felt relaxed and content in their company, a feeling that has become increasingly elusive for me in social situations. Like many, the past 18 months has instilled me with agoraphobic feelings: these are compounded by my life-long anxiety and fear of social embarrassment – of not wanting to become distraught or to lose control in public – something which, before consecutive lockdowns, I had in control. But that evening I was feeling good. I was happy to be with my friends, and I was happy that I felt at ease with them.

I got up to use the men’s. There, in the tiny, one-in one-out bathroom, I saw a mosquito moving slowly through the air, as though swimming in suspended syrup. My breathing became rapid; I broke out in a cold sweat. Was I about to have a panic attack? My heart began to pound. The mosquito slid upwards. Everything went white – presumably, I did too – and I collapsed. And I dreamt.

I dreamt of a wooded hill, with a winding path tumbling into a small village. Beside it, a deep, green, leafy valley. I was drifting through the woods, down the hill, to this place that felt familiar. I had a sense that the cotton-like clouds, the air, contained a presence: something that was ‘looking on’ as I descended toward the village, past tall trees, in misty light.

The apparent safety of this bucolic dream-landscape was seductive. It was beautiful; an idyll. When I regained consciousness, on the tiled floor, I wanted to keep dreaming. At the same time, there was something uncanny and eerie about the dream that left me ill-at-ease. It may have felt familiar, but I knew its landscape to be unreal. It reminded me of home; yet I knew it had never existed.

❦

A week or so before this incident, my debut collection of poems, Rotten Days in Late Summer (Penguin), was published. The collection centers around three sequences. ‘Diagnostics’ is about my dad, who passed away from a rare form of cancer when I was nineteen, and the fallout of this for his family; the sequence combines poems with prose fragments. ‘Treetops’ is a long poem, composed of 62 eight-line stanzas, broadly about my own experiences with depression and self-harm, and the difficulty of first articulating, and then finding support for, mental health conditions. Then there are several ‘Love Stories’ – three sonnets apiece, about love, desire and friendship. There are many stand-alone poems, too. Throughout the book, the landscape of the West Country hovers at the foreground.

I grew up on the Wiltshire-Somerset border, in a small village near an industrial estate and MOD base. The village is a stone’s throw from a valley, classified as an area of outstanding natural beauty. One of the criteria for such an area is ‘relative wildness’ – almost a contradiction in terms. Yet this criteria perfectly describes my experience of the area – and the community – in which I grew up. It was one of contradictions, or it was in-between things: both wealthy and not at all well-off, both patently ordinary and shot-through with mystery and folklore. Abandoned quarries and new-build housing estates; wildflower meadows and military bunkers; secret springs and barbed wire. We had a peculiar, sometimes absurd relationship to animal life: you might wake to a muntjac sleeping in the garden, or get chased by a herd of cows at midnight, drunk, taking a shortcut back from the pub. A sudden grass snake, gleaming in the sun, might cause you to skid off your bike, enroute to a shift at the egg-packing centre…

In the collection, I am interested in the idea of work, and its relation to environment, class, and gender. I am interested in the relationship between stereotypical notions of ‘hard work’ and ‘manliness’, how I saw these intersect with the cyclical culture of bigotry and conservatism which easily found its footing in that community so marked by sexual and racial homogeneity. The recurrent nature of violence, too, is central: violence against the environment, but also across generations, classes, and against strangers and ‘others’. But I also experienced the antithesis of all these things: a unique care toward animal life, a generosity of spirit and ribald humor, a subtle and real straining toward collectivism, and a sensual and often democratic – if clandestine – celebration of the body, that seemed to take succor from the earthy, luxuriant landscape itself. The poems in Rotten Days emerge from these tensions, from this ‘relative wildness’.

❦

The landscape and community foregrounded in many of the poems is, however, a remembered one. Two weeks after my dad passed away, I went to university. After I graduated, I moved back there for under a year, before going to Spain, and then London. My mum moved away from the area around this time, so I never had an easy reason to return. Over the past six or so years – when Rotten Days in Late Summer was taking shape in my mind – I had only been back to the area once or twice. A rift had emerged, between my life in the West Country as a child, teenager and young adult – the old friends who are still there – and my life now, in London, years later. Perhaps writing the collection was an attempt to understand the ongoing process of loss and departure, even as it was still happening.

Raymond Williams, the Marxist writer, academic and novelist, wrote extensively on the tradition of pastoral poetry and literature, noting that depictions of the pastoral – as a tranquil, eternal, innocent constant, inverse of the city, an alternative to war – invariably ignored, suppressed, or otherwise censored the economic and cultural reality of rural life, the conditions of work and labour which underpin that life, and the intricate social fabric that constitutes it. In Williams’ novel Border Country, the protagonist, having left his rural community to work in London, comes to realise that after leaving, he began to ‘pastoralise’ his home:

… the familiar shape of the valley and the mountains held and replaced him. It was one thing to carry its image in his mind, as he did, everywhere… his only landscape. But it was different to stand and look at the reality… He realised, as he watched, what had happened in going away. The valley as landscape had been taken, but its work forgotten. The visitor sees beauty; the inhabitant a place where he works and has his friends.

I now have a banal somatic explanation for the reason I passed out at that pizzeria in Walthamstow. But I’m curious as to why my dream-self, at that moment, went to this bucolic landscape. Not the difficult, contradictory, rich landscape of my remembered home – the version I have tried to render in Rotten Days – but to a pastoralised, gilded, somehow vacant version of it. Perhaps a false pastoral ideal is so prevalent in our culture that it can live dormant in one’s psyche. Perhaps – even knowing the troubling conditions that structure such an ideal – part of me is seduced by it. Or maybe, the dream should serve as a reminder, that if I am to truly encounter that place again – where I have spent more than half my life – I will only be able to do so as an inhabitant, never as a visitor.

Ralf Webb by Devin Blair

ROTTEN DAYS IN LATE SUMMER is shortlisted for the Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection. Buy your copy here.

All photographs © Ralf Webb