LONG READ 6

May 2021

On Being Photographed by John Deakin

By Esther Freud

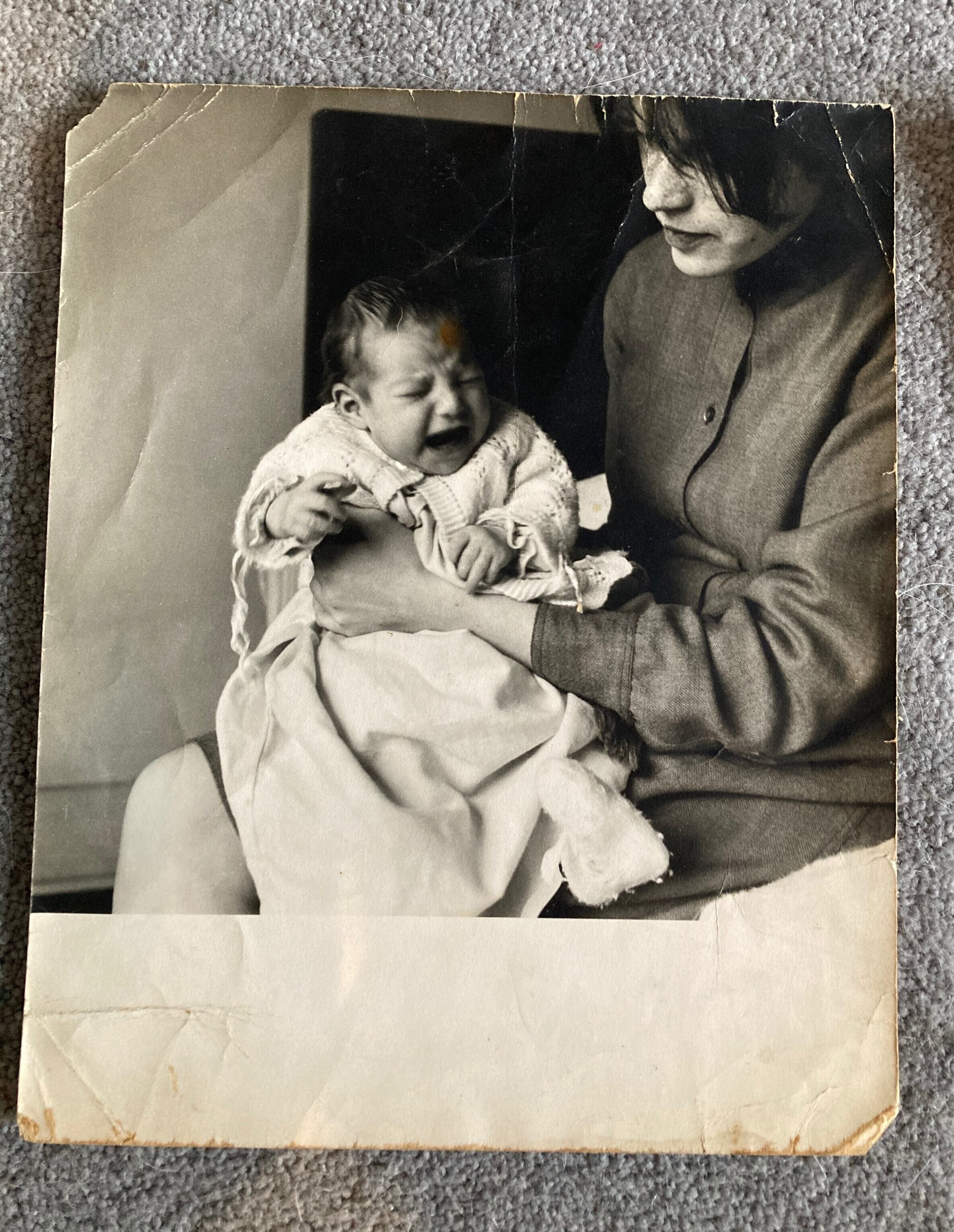

Photographs of Esther Freud with her mother taken by John Deakin

Author Esther Freud, has written one play and nine novels, the most recent of which, I COUDN'T LOVE YOU MORE, is published today by Bloomsbury. After publishing her second novel, PEERLESS FLATS, she was chosen as one of GRANTA's Best Young British novelists, and in 2019 she was made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. For the CHEERIO Long Read, Esther describes finding photographs of herself as a baby with her mother, Bernadine Coverley, taken by John Deakin, the great photographer of 1950s and 1960s Soho and friend of her father, Lucian Freud, and reflects on her mother's individuality, courage and strength as a young woman in the sixties.

I was searching online for an image that might work for the cover of my new book when I came across a photo by John Deakin. It was of a woman, the polka dot shoulder of her dress just visible, her hair, her makeup, her wistful expression - pure sixties.

My novel – I COULDN’T LOVE YOU MORE – is in part a sixties story. It was inspired by my teenage mother who came of age in the bars and coffee shops of Soho, where she met and fell in love with my father, Lucian Freud. Lucian was a friend of Deakin’s. I knew this because he’d been sent to take pictures of me as a baby. Where were they? I wondered. Abandoning the image of the unknown woman (she had, I discovered, been used for the cover of another book) I began searching through old photographs until I found, in their original wax paper sleeve, three creased and tattered prints.

I looked at them now as if for the first time. My mother, her face freckled and impassive, her smart clothes and lipstick failing to detract from the air of bleakness. They told a story, usually disguised. ‘Being fatally drawn to the human race, what I want to do when I take a photograph is make a revelation about it.’ Deakin once said. ‘So my sitters turn into my victims.’ It may be why I’d never really looked at them before, the only baby photographs I had.

Now that I was looking, I saw they’d almost certainly been taken at my father’s studio where he lived, and not as I’d imagined at the flat in Camden where my mother felt herself to have been banished. There were the familiar rumpled bed sheets and the crochet blanket, and me - my mother’s second child, although she was still only twenty - with the clenched fists and direct gaze of a father whose interest by then, she’d told me, lay elsewhere. The colours are muted, sepia tints, an emphasis on shadow, a large black rectangle behind both our heads, and in one, the beveled edge of a mirror reflected in the dark mass of her hair.

My mother came from an Irish/English family recently moved from London to Cork. She’d stayed, entranced by the freedoms of the post war generation of artists and poets, knowing, if she knew anything, that what she wanted was a different life from her parents. Heavily influenced by the doctrines of the Church – her mother was Catholic - and the privations of rationing, her parents were fearful for their eldest daughter, and in turn, she was afraid of them. Too terrified, certainly, to tell them when she became pregnant, certain she’d end up in a home. That her baby would be seized. So she didn’t tell them. Not the first time, or the second. And it wasn’t until several years later when a relative saw her with two small girls waiting at a bus stop and wrote to Ireland: ‘I didn’t know your daughter was married?’ that her secret was revealed.

‘Being fatally drawn to the human race, what I want to do when I take a photograph is make a revelation about it.’ Deakin once said. ‘So my sitters turn into my victims.’

‘You’ve made your bed.’ Came her father’s response. ‘Now you must lie in it.’ But by then, the girl in these photos had grown into a young woman. She had moved away from the sphere of Soho’s bohemia – so dangerous for the vulnerable – and was forging her own life. She’d cast off her passivity, let down her hair, and was making plans to embark on a new adventure – not only providing me with material for my first novel – HIDEOUS KINKY – but on a search for freedom and spiritual enlightenment.

None of the John Deakin images, it transpired, were right for the cover of my novel, which follows a different story to the one my mother embarked on. As I researched my character’s journey from the glamour of an affair with an older man, to a mother and baby home on the outskirts of Cork, forced to work long hours, cleaning and toiling, for the privilege of being ‘looked after’ by the nuns, I was sickened by the cruelty inflicted on so many thousands of women. When I look at my mother, captured here, at what must have been one of her very lowest times, I see the courage, and the strength it took to keep those secrets, and forge ahead with her own, most individual life.

Esther's latest novel, I COULDN'T LOVE YOU MORE, an unforgettable story of mothers and daughters, wives and muses, secrets and outright lies, is published by Bloomsbury today. Get your copy here.